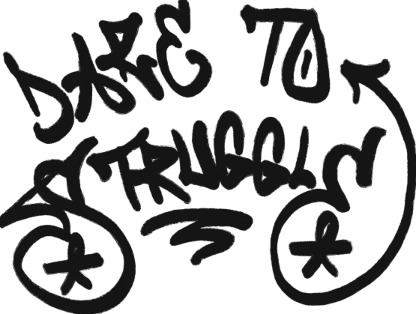

A call to action from Dare to Struggle – Chicago

For more than 6 months now, Dare to Struggle – Chicago has been going out to Cook County Jail, talking with inmates and their loved ones about the horrors behind its walls. The conditions people are forced to endure are deplorable. Food and water that make inmates sick, scalding hot showers, mold infested toilets, and freezing temperatures in the night time are just the start. Mice, rats, and roaches run rampant through the cells in nearly every division. And the list goes on. This alone would drive any normal person to the brink of insanity. But to make matters worse, if inmates wanted to try to distract themselves from this reality through any kind of mental stimulation, most are often only provided limited access to the law library. Classes and programs are considered a privilege only for a select few out of the 5000 plus inmates, who are paraded in front of the news cameras and become the face of CCJ when politicians and higher-ups come in for a tour. For the vast majority of inmates, their days inside CCJ are spent doing nothing at all. Pictures of loved ones, drawings inmates make for things like art therapy, and books sent in from the outside are often confiscated. Inmates are often shackled like slaves for no justifiable reason.

On top of these conditions is the rampant, unchecked mistreatment and abuse from the corrections officers (COs. Inmates are verbally abused by COs trying to act tough on the daily. Inmates are punished in a whole host of ways by COs, denying them “privileges” like visitations, phone calls, and using the microwave. They throw inmates into segregation or the hole for nothing, while the head of the jail, Tom Dart, tells the world CCJ doesn’t have solitary confinement. If COs can’t get their licks in on an inmate that’s pissed them off, they can throw an inmate in a cell with their opps or bribe other inmates to attack them. COs not only get away with physically assaulting inmates but sexually abusing them too.

Every day is a humiliation ritual for those inside. Men and women can spend years of their lives living with this reality, while they wait and wait for their day in court. As the jail tries to break inmates mentally, the mental health they offer is a joke—if inmates even get access to it or are believed by COs when they say they need help. Inmates’ medical needs are often ignored or neglected, leaving inmates with injuries or infections to worsen, or for them to succumb to medical problems and die. When we step back, it becomes clear as day who the oppressed are and what the oppressive system is. Yet, inmates will often turn on each other instead, bringing in beef they have on the street with another inmate, picking fights over petty shit, parasitically extorting their fellow inmates, and at worst: raping, torturing, or killing one another.

So what are we going to do about this? People inside live the above reality, a hell on Earth. Their loved ones on the outside hear the stories and worry about them. What’s stopping people from coming together and figuring out how to fight back?A lot of people have been conditioned to have faith in the system. Many are hopeful that politicians will suddenly care about the plight of inmates in the jail, or that appeals to elected officials’ consciences will change their minds. There’s also the fear of reprisal and COs coming after inmates in retaliation for speaking out. But mainly, it’s a deep-seated nihilism that holds people back: the idea that there is no point in struggling and striving because nothing ever changes. This thinking is exactly what the jail authorities, the politicians, and the people at the top of society want us to believe. They train people in this type of thinking to keep people dependent on their system and from getting out of line. Part of how they have engrained this thinking in people’s heads is stripping them of any historical memory of people standing up to oppression, and inmates standing up to the conditions they suffer under. The fact is, there is a rich history of inmates taking a stand, fighting back against conditions and injustice, and forcing the system to concede to their demands. Through difficult struggles, inmates were not only able to make significant changes in the jails and prisons, but also transformed themselves in the process, from a criminal mentality to a revolutionary mentality.

When you dare to struggle, you dare to win

There’s a hidden history of prison struggles going back to the Nation of Islam (NOI) in the 60’s. From its inception in the 1930’s, the Nation saw the prisons and jails as an arena of political struggle. Coinciding with the Great Migration, when masses of Black people moved to urban centers in the North fleeing the Jim Crow South, police, prisons, and jails became the main tools of oppression against Black and other oppressed people. The Nation quickly identified this systemic oppression and its members inside the prisons began organizing themselves. As the prison populations grew, so did the Nation’s membership and influence inside the prisons (Malcolm X was recruited while in prison by his brother, where he then met other NOI inmates and began his transformation from a petty criminal to a Revolutionary activist for the NOI). Muslim inmates faced discrimination from prison authorities in a number of ways, such as prohibiting prayer, banning religious texts, and neglecting to serve halal meals (the religious diet of Muslims). The NOI inside, able to transcend the bullshit and come together, took up early fights against these discriminatory practices through acts of resistance including hunger strikes, sit-ins, disruptions of solitary confinement, and litigation against prison officials.

Not only did they fight for the Black Muslim inmates, but also forced the hand of prison authorities to allow inmates to get access to legal texts (if you use the law library, you can thank the NOI for that), recognize and respect the rights of prisoner organizations, create educational opportunities and programs for inmates, and address poor living conditions. Organization on the outside allowed for the NOI to publicize these struggles to a wider audience among the masses of Black people through their newspaper Muhammed Speaks, exposing both the realities of prisons and jails and the struggles against them. NOI members left the prisons to become activists in the streets like Malcolm, transforming themselves behind the prison walls and leaving any kind of criminal life they may have had in the past.

Attica Means Fight Back!

In the 1960s-70s, the population in jails and prisons began to explode. Aggressive policing of Black and Latino neighborhoods in the cities coupled with unemployment, the growing drug economy, and continued racist discrimination, threw thousands of young people into the prison system. New revolutionary organizations, inspired by Malcolm’s example, had emerged, such as the Black Panther Party (BPP) and Young Lords Organization (YLO), a Puerto Rican revolutionary organization. The politics of these groups influenced the great mass of prisoners inside, with the BPP even establishing its own prison chapters at the directive of BPP leader George Jackson. At this time, inmates across the board were more organized, whether it be on lines of religion, nationality, or ideology. In some instances, this would lead to conflict among inmates, with prison organizations operating more like gangs beefing with one another.

In 1971, inmates in the Attica State Prison in upstate New York rose up against the prison authorities, their poor living conditions, and repression of their political rights, exposing to the world they were being “treated like beasts.” On September 9, 1971, 1,281 of the approximately 2,200 men rebelled against the prison authorities, taking control of the prison, and holding 42 staff members hostage. During the four days of negotiations, authorities agreed to 28 of the prisoners’ demands, but refused to fire the warden and grant amnesty for those engaged in the prison takeover. The governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, refused to meet with inmates at their request, and instead ordered armed officers to invade the prison, massacring 10 correctional officers and 29 inmates in the process.

There are plenty of things we can learn from the Attica rebellion. The rebellion occurred during a time of intense political struggle across the US (and world) against the Vietnam war and racism at home. People were identifying with the people of China, Vietnam, and other struggles around the globe against colonialism and imperialism. Inmates leading the uprising were steeped in this political climate and were organized along these political lines, having drawn up demands and engaging in political protest inside the prison prior to the rebellion. Lying underneath, the conditions of life in Attica were worsening. The prison, only built for 1,200 inmates, had reached a total of 2,243 by the time the rebellion had popped off, with inmates living on top of one another. In describing the conditions of life, historian Howard Zinn writes, “Prisoners spent 14 to 16 hours a day in their cells, their mail was read, their reading material restricted, their visits from families conducted through a mesh screen, their medical care disgraceful, their parole system inequitable, racism everywhere.” All of this and more were the conditions that led inmates to revolt. So on that September day, when some inmates had an argument with a guard and COs later came to throw two of them into solitary, other inmates resisted and began the takeover.

We remember Attica today because of the courage of the inmates, and because it shined a light on to the brutal conditions prisoners in the US face. During the uprising, inmates spoke out on live TV about the torture at the hands of COs, inhumane living conditions, and brutal treatment of inmates by both the prison and legal system. Attica sparked more rebellions elsewhere and a national movement of people on the outside to take up the cause of prisoners. It put the prison struggle on the map for the whole world to see. Not only did it force the system to make substantial changes to the treatment of prisoners and general prison conditions, but also to make changes to things like parole. And while the rebellion was violently put down, those inmates took a bold stand and made the ultimate sacrifice that inspired millions in the decades to come. Today, Attica holds a special place in the hearts of the oppressed across the globe.

The SHU and Pelican Bay

The prison movement made both advances and retreats in the years following Attica. While the system was forced to make changes that respected the rights of inmates, it also took precautionary measures to try and prevent inmates from again becoming a force they had to reckon with. In the 1980s, California prison authorities began to massively expand their prison system. The so-called War on Drugs launched in the 70s-80s, creating an explosion in the prison population, with Black and Latino men targeted in police arrests and hit with long sentences for non-violent drug offenses. California was no stranger to the prison movement and uprisings and knew very well that if too many inmates got together, they would start to rebel against the system. One way to try and prevent this was California prisons’ long time policy of dividing and segregating inmates by race, leading to stoked racial tensions inside the prisons, but increasingly, authorities began to use solitary confinement as a means to keep inmates divided.

In 1989, California opened the Pelican Bay State Prison, a so-called state of the art prison with a new kind of indefinite solitary wing known as the SHU (Security Housing Unit). The SHU was designed to hold prisoners who were determined by authorities to be members of “prison gangs” and posed an “internal security threat” to the prison authorities. These inmates would be removed from the general population and placed in solitary for the remainder of their sentences, many in solitary for decades. Black inmates caught reading books like Soledad Brother or Blood In My Eye by Black Panther leader and prison activist George Jackson, or Latino / Chicano inmates found with drawings or symbols of Aztec warriors, would be classified as internal threats, transferred to Pelican Bay, and placed in the SHU. Thousands of inmates not only suffered from the decrepit conditions and abuse, but also the psychological torture of the SHU, having no human contact for years besides COs who would move, restrain, or beat them. Visitors couldn’t even be in the same room as inmates. Usually having to drive hours to see their loved ones inside, families could only talk through glass to inmates for their one-hour visit, once a month.

Despite their solitary confinement, inmates in the SHU devised ways to communicate with one another, through coded messages and passing small handwritten notes between cells. After some years of planning, inmates in the SHU managed to organize a hunger strike in 2011, demanding an end to their indefinite solitary confinement, and another strike in 2013. Inspired by the 1981 Irish Republican Army (IRA) hunger strikers who fought inside British prisons against conditions and violations of their rights, SHU inmates saw the tactic of a hunger strike as a way to not only bring prison authorities to meet demands but also to get more public attention on the struggle of prisoners. News of the strike spread, and inmates in other prisons began to join in, adding demands like clean facilities, better food, and better access to books. At its peak, some 30,000 inmates across the state of California joined the 2013 hunger strike which lasted for approximately 2 months with different degrees of engagement. The strike gained national attention and put a spotlight on California’s use of solitary confinement and its poor prison conditions. The California strike inspired others to take up the struggle even after it had ended. In 2014, over 1000 immigrants, detained by US Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE) at the notorious Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington, went on a hunger strike for 56 days to protest their confinement and the horrific conditions in the facility, exposing people to the struggle of migrants captured by ICE who were forced into the same conditions as inmates in the jails and prisons. In 2015, due to the struggle of prisoners, California was forced to terminate indefinite solitary confinement and greatly reduced the number of individuals in solitary as a whole.

While horrific conditions inside California jails and prisons persist, the hunger strike dealt a blow to the system and forced it to concede to inmates’ demands. Even under the harrowing and nearly impossible conditions of solitary, inmates were still able to organize themselves to fight back. Prisoners in Pelican Bay, who would normally be considered enemies, got together to draft an “Agreement to End Hostilities” document stating inmates would not fight each other. An outside support network helped spread the word to other prisons and raise the demand of prisoners in the streets. This kind of coordinated inside-outside strategy built a broad movement among different sections of society, a movement much needed and severely lacking today.

What is to be done?

All of these examples are really one historic continuation of the prison movement. Organizations come and go, capitulate, and can be sabotaged by the enemy. Inmates who stand up and speak out can be retaliated against. These are the realities of the struggle to change the world and fight oppression. But one thing remains certain: no one besides the masses of people will make the kind of change we need. Inmates in the aforementioned examples were never begging for changes to be made. Inmates were organized to fight against the prison authorities and the conditions they imposed.

Today, we are sorely lacking the kind of organization required to deal a real blow to the mass incarceration machine. However, we are not lacking historic examples and conditions that continue to force inmates into action. Recently, in the Winter of 2025, inmates inside New York prisons stood up and rebelled against conditions in several prisons across the state, requiring the National Guard to be called in to stop the unrest. As far as we are aware, these rebellions were mostly spontaneous reactions to the conditions inside and didn’t raise a coherent list of demands or have much outside support. What is required is the kind of organization that can lead both inmates and people outside to really challenge the conditions and mistreatment prisoners face.

If inmates at Cook County Jail and their families are ready to put an end to the misery, the horrific conditions and mistreatment they face, an organized movement is needed. This summer, Dare to Struggle is issuing this challenge to inmates and their loved ones to take up the call to build this kind of organized movement.

Even though the above examples were mainly about prisons, let’s be real: Cook County Jail is a prison pretending to be a jail. CCJ is the largest single site detention center in the US, with many of its inmates spending years inside waiting for trial. The jail population is projected to increase under state’s attorney Eileen O’Neill Burke’s so-called “war on guns,” where she intends to pursue detention and harsh sentences. CCJ calling itself a jail is not an excuse for inmates to bow out of organizing themselves, especially if they want shit to change.

The first step in building a movement that challenges CCJ is speaking out. Families and loved ones of inmates need to start publicly speaking out against the jail and the crimes they are a witness to. Tom Dart gets away with selling all of his “programs” for a small number of inmates when the suits and news cameras are walking through, but we need to expose the reality of the vast majority of men and women inside CCJ. Families need to defiantly oppose the bullshit standards and policies CCJ imposes like the denial of visitations or the confiscation of mail and care packages. Thousands of people in Chicago and in Cook County, former inmates and their families, have been negatively impacted by the jail and need to be brought forward in the fight against it as well. People on the outside must identify and go after the people who hold the levers of power at the jail, namely Sheriff Tom Dart and his cronies. In the Fall of 2024, Dare to Struggle drafted a list of demands based on our conversations with inmates and their families that can be used to fight around. The outside needs to have meetings to figure out how we are going to move, how we are going to embarrass and expose the authorities if they don’t meet our demands, and how we are supporting those inside. The outside needs to be built to support the inside and begin to see itself as an essential component in the struggle against the jail.

Inmates at CCJ need to come together and distinguish friends from enemies. People come inside from different blocks of neighborhoods or different parts of the city. People are different nationalities, straight or gay, different religions, etc. The COs use these differences to pit people against each other. We all know the stories about COs throwing people in cells with their opps or people they have problems with in order to stoke this tension. But everyone on the inside has a common enemy: Tom Dart and CCJ. Settling petty beefs between inmates is essential, and the disunity only serves the jail by keeping people divided and fighting one another. Inmates should create a collective culture among one another, and unite against inmates in the jail who prey on others and don’t stop when instructed. Inmates should be brought together on the basis of having a common struggle against the jail. Get together with people, read and discuss the Cracks At Hotel California newsletter and other pamphlets sent in by Dare to Struggle. Let us know what you think. Send us reports about the conditions on your deck and in your division, what people are up against, and let’s make noise together. If you are transferred to another jail or prison, spread this organization to the other places inmates might go to. If this is something you want to do, get in contact with Dare to Struggle and we will work with you.

From the criminal mentality to the revolutionary

Most importantly, inmates must transform themselves and commit to the struggle. Whatever people did or didn’t do on the outside, everyone inside CCJ is encouraged to act and think like a criminal. The desperate conditions force inmates to turn on each other, rob, steal, and extort one another. For oppressed people, the entire system encourages and fosters a criminal mentality, a “get mine,” “me first,” dog-eat-dog world. This has got to change, and it can only change through an intense personal struggle with oneself. Before Malcolm became Malcolm X, he was a petty criminal who stole, robbed, pimped, and sold drugs (going by the name of Detroit Red). It was during a stint in prison where Malcolm was recruited into the NOI and began the process of deep, personal, and political transformation, changing himself from Detroit Red to Malcolm X, who left the prison and would become a revolutionary leader that shook the system to its core. George Jackson, the revolutionary Black Panther leader in California, went into prison for allegedly robbing a gas station for $71. He would enter the California prison system and learn revolutionary ideology, reading Marx, Lenin, and Mao, stating “they changed me.” He would go on to be a central figure in the prison movement and was later assassinated by prison authorities due to his organizing efforts. And to get a little closer to home, in 1968 a young Puerto Rican gang leader named Jose “Cha Cha” Jimenez entered Cook County Jail for a 60-day stay for possession of heroin. During this time, Cha Cha began to read revolutionary literature and decided he would dedicate himself to fighting oppression. While inside, Cha Cha stood up for other inmates, helped translate for Spanish speaking inmates inside and educated inmates on their rights. Cha Cha left CCJ and would go on to turn his street gang into a revolutionary organization called the Young Lords Organization. He continued to fight against oppression until his passing at the beginning of this year.

This kind of transformation is not just personal, it’s political, and one where people are transforming themselves not only to help themselves but to help others change as well. This transformation is about clarity: seeing what’s really going on and helping others see clearly in the process.

We know we have our differences. But we have a common struggle against the people who have captured you, the people who serve you shit food, the people who humiliate you, the people who neglect you, beat you, and set you up. It’s time to make real change at CCJ. You in? Hit up Dare to Struggle to get involved.

Support the newsletter! Venmo: @dtschi