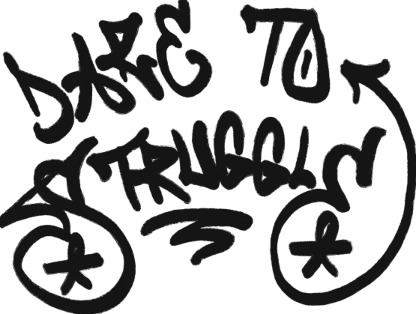

Dare to Struggle has been discussing questions surrounding organizational function, and a recent episode in our organization made us feel the need to put some principles on paper. In Spring 2023, we brought in some prospective members, and a couple of them who weren’t committed to our mission tried to pull our group’s work in a different direction, factionalizing, shit-talking, and otherwise acting in unprincipled ways in the process. This was a case study in opportunism—attempting to change our organization by substituting our politics for an easy way out of the struggle instead of doing the difficult work of developing ties and organization among oppressed people. Our purpose as an organization is to go to the masses and organize them in collective struggle. We’re literally called Dare to Struggle. Drawing on our recent experience, we are putting forward these principles as a model we’re practicing and hope to discuss with like-minded organizations and individuals.

1. Put all questions, disagreements, and criticisms on the table to be aired openly within your organization. Today among groups on the Left, gossiping, shit-talking, spreading rumors, and factionalizing are all standard practice. Who hasn’t heard members of leftist groups like DSA and PSL routinely talk shit about their own organizations? Even if these organizations were to be taken seriously in the first place, the shit-talking is unprincipled. Beyond any particular organization, this is the culture leftists are trained in and take with them to every dead-end leftist organization they join. This behavior is also how FBI agents wreck political groups, and it’s a playbook the Left has effectively taken up today. Indeed, the contemporary Left has adopted the tactics of COINTELPRO as their own, not because they’re government agents, but because they’ve adopted opportunism as their modus operandi. (For a lesson on COINTELPRO, watch the 2019 movie Seberg to learn how the FBI created a rumor about Jean Seberg’s personal life to undermine the Black Panther Party and drive her to suicide.)

In Combat Liberalism, Mao Zedong wrote that one type of liberalism is “to indulge in irresponsible criticism in private instead of actively putting forward one’s suggestion to the organization. To say nothing to people to their faces but to gossip behind their backs, or to say nothing at a meeting but to gossip afterwards.” How do we prevent this corrosive shit from holding sway in our organizations? People shouldn’t talk shit or gossip about their own organization. Questions, disagreements, and criticisms should be aired openly, discussed and debated, within the organization you are part of, not gossiped about outside of it, and this should be a part of daily practice.

2. “Capacity” should be viewed as the ability to carry out work from a collective perspective, not as individuals. “I’m at capacity”—who hasn’t heard this from a leftist activist? Rarely do they give legitimate specific reasons, instead using some hazy notion of “capacity” as an excuse to not commit to the struggle. It’s not that people’s personal issues don’t matter, but if we want to get anything done we can’t just leave our responsibility to the people behind when things get tough. What’s striking is that “I’m at capacity” is never uttered by the masses we work with—people who don’t have money, who have to look after their kids, who have a host of health problems, and who deal with many other ways the system keeps people down. If these issues prevent individuals from taking on a higher level of commitment, we should find ways to work with them and find out what they can do. But this bastardized concept of “capacity” starts from oneself, not the needs of the people oppressed by the functioning of capitalism. Leftists will even project it onto the masses in a condescending way, arguing, in effect, that the masses can’t be the force for change because of what they’re up against.

The truth is the exact opposite: the people subjected to the worst of this system are the primary force for change. We strive to serve these people and take seriously our responsibility to them. When we inevitably struggle as individuals to carry out our work, we should rely on each other for collective support. If anyone is ever in need of something, materially or emotionally, we do what we can to provide that to allow us to continue our work.

3. Leadership should be determined by commitment to the masses and the ability to advance the struggle, not individual identities. How do we bring people forward as a force for change and raise them to the level of leadership? Appointing people to any role based on identity (race, gender, nationality, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t really answer that question. People function as leaders because of what they do, not who they are. Many leftists will (correctly) criticize the ruling class for using identity politics to try to fool people into thinking that having a token Black mayor will improve the conditions of Black and other oppressed people. In New York City, for instance, police brutality and mass incarceration have only gotten worse with Eric Adams in charge and Keechant Sewell as police commissioner. But it’s hypocritical to have those criticisms of the ruling class and then appoint people to leadership in political organizations based on their identity. When we fixate on identity categories as qualifiers for leadership, we stop assessing the work of leadership based on their strategic vision, actions, and results. Instead of identity, we should determine someone’s capability for leadership based on their commitment to the people and their ability to bring the masses forward as a force in challenging their oppressors. We certainly need revolutionary leaders from oppressed backgrounds, but the key thing is the content of their leadership—that they’re revolutionary leaders, not that they’re this or that identity.

4. The internal dynamics of an organization aren’t the decisive factor—what we’re actually doing in the world is, and this should be what defines the internal dynamics. The focus of Dare to Struggle is on going to the masses and organizing collective political struggle. That’s what defines us. How we establish leadership, make decisions, and evaluate our work all have to serve that function. Problems arise when organizations divert too much attention to procedures and structures, pulling them away from the work they’re supposed to be doing. This could mean rehashing settled questions about how a group functions, including who’s in charge and how work is carried out. Whether through elaborate voting/decision-making procedures or delegating work into “committees” that don’t communicate with each other, time and effort spent on secondary tasks takes people out of actually engaging in mass struggle. We certainly need room for discussion and criticism and we need formal procedures for some things, but this all has to be in service of advancing our political work, strengthening internal unity, and taking on the enemy.

5. Leadership and structure are important, but there should be no obsession with titles. Huey P. Newton could rightfully call himself Minister of Defense because he pulled guns on pigs. We see a lot of leftists these days self-appoint titles that invoke the Black Panther Party and similar groups to stroke their egos and pose as revolutionaries. It’s juvenile to name yourself chairman or minister of anything when it’s just you and a handful of other “comrades” spending all your time talking to other leftists and handing out free food instead of going to the masses and bringing them into collective struggle week after week. Indeed, we’ve even seen the absurd scenario of organizations of five people where everyone is a minister of something. Certainly large organizations need named roles, but we have generally used as little formality as possible given our present small size. We may need to create some official titles and roles as we grow and step into more political battles, but we’ll only do so if it’s needed to advance our work, not to boost our public image as individuals.

6. The process for relating to other organizations should be through unity – struggle – unity. After Fall 2022, Dare to Struggle published a summation (available at daretostrugglenyc.org) of the struggle over contaminated water in the Jacob Riis housing projects as a basis for discussing what we were doing and learning from other individuals and organizations engaged in struggle. We sought out genuinely curious but also critical discussion. Instead, the most common response we got was that “we’re doing the same thing,” a response which smoothed over any differences rather than having principled, critical discussions that would get us to a mutual understanding of what, if anything, we could unite on. We did meet several individuals and organizations that we were able to have meaningful discussions with, and we hope to continue to discuss and collaborate with them. What set them apart was a willingness to learn from each other and get into whatever differences there were.

Who hasn’t heard a leftist talk about wanting to “link and build”? Build what? On what basis do you build without hashing out important questions and understanding and resolving differences? To us, “link and build” just sounds like corporate networking for leftists and backscratching between small groups. Instead of transactional thinking and empty platitudes, organizations should actually have critical discussions together about what they’re doing and what they hope to accomplish to achieve a higher unity around how we really unite to advance the struggle.

Suggested Further Reading

- War at Home: Covert Action Against U.S. Activists and What We Can Do About It by Brian Glick

- A Black Professor Trapped in Anti-Racist Hell by Vincent Lloyd

- Combat Liberalism by Mao Zedong